Millions of Kazakhs have been deprived of their incomes during the state of emergency introduced by the country’s government to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. Among these people are officially-registered employees, private businessmen and entrepreneurs, and the so-called “self-employed” – those engaged in work in the informal sector. Fergana’s correspondent spoke to representatives of each of these sections of society and asked them how well they think the government is fulfilling its promise to support the Kazakh public through these testing times.

The most important thing: not to get ill...?

Akerke (pseudonym, at her own request) works in a bank in Almaty. Just before the start of spring she fell ill with a viral respiratory infection and took some time off sick. After recovering, she was placed on leave due to the lockdown, although she argues that she could easily have worked from home. “For some reason they put me on unpaid leave, despite the fact that everyone else was working from home. It’s a bit unfair, I could have worked from home too,” she laments.

Akerke attributes her bosses’ decision to the fact that she is pregnant. Along with a small number of other colleagues, she is therefore considered to be in a risk group and was placed on unpaid leave.

Fortunately, her employer agreed to provide her with a monthly payment of 42,500 tenge ($96 – equivalent to emergency payments promised by the government to those who lose their incomes as a result of lockdown measures – see below) on account of loss of income during the state of emergency.

“Of course, it is some consolation that I will receive 42,000, but it’s not the 200,000 tenge ($455) with which I normally feed the whole family,” Akerke noted sadly.

Akerke’s family is made up of three people: besides the bank clerk herself, there is her 58-year-old mother and her 77-year-old grandmother. Both women require medication totalling 7,000 tenge ($16) each day. Medicinal products also needed for Akerke’s future son. Following the introduction of the lockdown, the mother-in-waiting can no longer afford the vitamin supplements that she used to buy for herself and her child. “I’m extremely worried right now. As a single mother-to-be, I never asked anyone for help, but now I don’t know what to do,” she says.

Akerke doubts that the 42,500 tenge payouts will be enough for her family’s needs and plans to plant a vegetable garden in her front yard in order to at least save a little money on food. “I guess I’ll sow potatoes,” she says. “What else can I do? We can’t starve to death.”

Another Almaty resident by the name of Nurlan is more optimistic, despite the fact that he too has been left bereft of any income. Nurlan leases a tyre repair workshop. “Everything came to a sudden stop around 22 March. There’s no work, nothing to feed the kids. I have four children and loans to repay. So far we still have some of our old food supplies left. But I don’t know how things are going to go, we’ll just have to see. My wife is also without work, she’s looking after the kids. The most important thing is to pull through this thing somehow, but there’s nothing to worry about – people have gotten through difficult times before and we’ll get through this one too. The main thing is not to get ill. Health is more important than financial problems,” says Nurlan.

As for Gulnara Esentayeva, who runs a school canteen in the capital, Nur-Sultan, she doesn’t hide her anxiety. She is worried about employees who have been left without work after the decision to send all schoolchildren in Kazakhstan on holiday early and close the country’s schools. “In my team alone there are 18 people, and that’s just one school – how many schools are there in the whole city?! Before they could earn a little extra cash in some café or something but now they can’t do this. Everything is closed now, they work by delivery only and cafés and restaurants have their own cooks. No one is hiring,” says Gulnara.

According to her, some of the canteen staff are unable to obtain the 42,500 tenge payouts, so she and some others are helping them out with food parcels. “We’ve distributed a bit of food, but it’s only enough for 1-2 weeks. Some of them are even starting to run out already. They all have loans to pay back, rent payments to make. Some are being kicked out by their landlords. Everyone is struggling, some of them are the only breadwinners in the family,” she says.

Who qualifies for a payout?

On 25 March the Kazakh government announced that those placed on unpaid leave in connection with the state of emergency would be entitled to social assistance payments of 42,500 tenge ($96) a month. But in order to receive this payment, employees were required to have had at least three months of social insurance contributions paid in by their employers. The allowance was to cover employees of medium-sized, small and microbusinesses only. Their employers would have to present local employment offices with documents confirming the loss of income. Not all employers, however, rushed to do this, and some had absolutely no desire to grapple with state bureaucracy.

Numerous categories of Kazakhs working in the country’s informal sector remained outside the scope of even this meagre safety net. One of them is Aynur Malikova, who was engaged as a housekeeper up until the lockdown. “I worked informally. I was paid each day, in cash and without insurance contributions. When the lockdown came in, I lost my job. I went back to my mum’s house in Chilek (a town in the wider Almaty region) – it’s not safe to stay in Almaty without work. We’re waiting until the 15 April, but it’s not certain that it will all (the lockdown) be over then,” she said. (Note: On 10 April, after this article was originally published, it was announced that the state of emergency and accompanying lockdown would be extended until the end of April).

Aynur still has her rented apartment in Almaty. “I need to pay rent for April. Right now I don’t have any kind of income, and however much I want to I can’t pay the rent. All my things are still in the apartment, I left the city hoping that the lockdown will end on schedule and that I can soon go back,” she said, angry that the government was not helping all those who have lost their incomes.

Soon, however, things changed. President Tokayev ordered the government to extend the list of groups qualifying for benefit payments during the state of emergency. To it were added sole proprietors (1.5 million people around the country), private lawyers, notaries, bailiffs, mediators (more than 2,000 individuals). Now freelancers engaged on civil law contracts too can make a claim (180,000 people), as can the self-employed if they paid the ESP (“Unified Aggregate Payment” – a way for self-employed individuals to make their own combined income tax, social insurance, health insurance and pension payments) last year.

Here we need to explain a little more fully what the term “self-employed” really means in the Kazakh context. In Kazakhstan, around 440,000 people were officially registered as unemployed last year. Recently, officials have begun calling those not registered on the labour market and engaged in the informal sector “self-employed” (samozanyatye). At present there are more than two million such “self-employed” individuals in the country. Experts point out that the existence of this category is a great convenience for government officials since it allows them to present lower unemployment figures in their reports. Last year, the ESP was introduced as a special tax for the self-employed, working out at $6 a month for urban residents and $3 for the rural population. Examples of potential ESP taxpayers include taxi drivers, mechanics and electricians, carers and housekeepers, and those engaged in the small-scale sale of home-grown produce.

Following the extension, the samozanyatye will also be entitled to a small allowance. “The government’s hand was forced by public pressure, because otherwise it could have led to social upheaval and food riots,” says the well-known Kazakh economist Arman Bayganov. “It was needed to stop people from starving to death. But they (the government) forgot something: this money is not enough for a family to live on. Families have children. How can a family with three children survive on 42,000 tenge, and in a rented apartment to boot?”

The government, Bayganov argues, “loves to make pretty speeches about an average wage of 200,000 tenge, so it should provide families with assistance at an equivalent level”.

Websites that crash

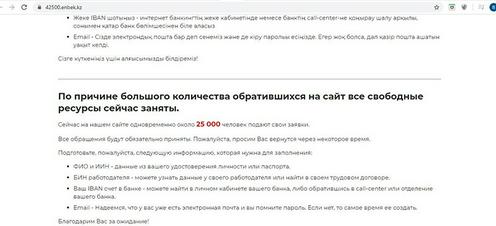

Later events, however, showed that even the 42,500 tenge allowance was not so easy to obtain. First of all, due to the surge in visitors, Kazakhstan’s electronic government website for benefit claims, egov.kz, crashed (Editor’s note: on repeated occasions during the translation of this article, we have attempted to check information on egov.kz but not been able to access the site). Claimants flocked to the country’s citizens’ service centres, showing little concern for social distancing or any other COVID-19 preventive measures. Seeing that the situation was getting out of hand, state officials rushed to set up a new site 42500.enbek.kz in order to relieve the pressure. But this system too failed to cope with the traffic. The government then promised to launch a Telegram bot.

Simultaneously, the Ministry of Labour announced that recipients of social benefits would be required to open a special bank account, which led to crowds of people amassing at local bank branches. Only at the start of this week did websites on which it is possible to apply for the emergency allowance manage to load successfully and the Telegram bot start to work. Meanwhile, realising their error, government officials announced that it was not necessary to open a special account after all – any bank account would suffice. Those who had no bank account at all would be allowed to apply anyway, but were given a month in which to open one.

Thus the rules were chopped and changed daily, while problems in obtaining the allowance remained. Nevertheless the labour ministry appeared to blame the public for the websites’ malfunctions, with labour minister Birzhan Nurymbetov complaining that people were spending too long on the system by clicking on the wrong pages and sending in more than one application. (Note: After this translation was originally published, Nurymbetov has issued a statement explaining delays in processing claims for the 42,500 tenge allowance with reference to the fact that the government has received nearly 5 million applications so far, and that checking such a volume of claims for duplicates, errors and fraud takes time.)

While those used to earning 2-300,000 tenge a month languished in long bank queues for the sake of a sum four or five times smaller, the government was promising people “missed” by these payouts food packages. According to the Almaty social welfare office, some 5,500 people received such packages on 7 April, including pensioners living on their own and those receiving ASP (Targeted Social Assistance) at the end of 2019 but who did not meet the new requirements in 2020. Nevertheless, judging by the list of categories of recipients approved by the Ministry of Labour, this one-off aid in the form of two parcels of food to last until the end of the lockdown (however long that is) does not seem to be intended for all. Those who qualify for it are: children between 6 and 18 years of age who receive targeted social assistance; individuals of all ages with class I, II and III disabilities, excluding those permanently residing at social-medical facilities, as well as these individuals’ parents and the guardians of disabled children; and finally the unemployed – but only those registered at an employment centre. In effect, the labour ministry’s rules meant that a family with three children in which the parents are not officially registered as unemployed has no chance of obtaining even these “consolation prizes”. The municipal authorities in Almaty have, however, assured needy families that if they contact the city’s call centre then they too can make a claim for one of these hampers.

Another kind of consolation has been offered by banks – loan-takers have been allowed to defer payments for three months without normal penalties being applied. But even here there was a hidden catch – under some banks’ terms and conditions it turned out that deferred payment would increase the overall cost of the loan.

“When deferments (on loan repayments) are granted, the money is not simply written off, it doesn’t just disappear. It still needs to be paid back. It just means people don’t have to worry about their credit score,” explains independent banking expert Nurzhan Biyakayev.

The real problems, Biyakayev says, can come from debt collectors and private enforcement agencies. “Although debt collectors and enforcement agencies don’t have court orders, complaints are still coming in from bank customers that they are continuing, maybe even more actively than before, to harass debtors and demand that they pay back all their loans. During a state of emergency this is not right and it creates tension. This is something that needs to be dealt with,” adds Biyakayev.

What will happen to businesses in half a year’s time?

Business-owners whose financial position has suffered due to the state of emergency have been granted deferments on their tax payments. Yet experts are warning that this may not be enough to solve the problem. “How will they be able to pay their taxes when the deferment period comes to an end? They have no revenue and taxes may increase. I would advise that they be totally exempted from having to pay,” says Arman Bayganov.

Entrepreneurs in Almaty are currently scared to predict what will happen to their businesses two months down the line, let alone six.

Almaty resident Olga runs a private kindergarten. 15 of her employees are sitting at home without work due to the lockdown. “Right now everyone is in shock. Three of my employees are single parents. Almost all of them have loans to pay back. My husband and I both work at the kindergarten and have been left without work. We have a mortgage to pay and three kids, plus we have to pay rent for the kindergarten premises. So far they (the authorities) have promised us nothing,” Olga recounts.

She says that the kindergarten’s accountant plans to submit the relevant documents to the employment centre so that staff can obtain the 42,500 tenge allowance. At present, Olga cannot see any hope for the kindergarten. “The risks are obvious – if we can’t operate then we’ll have to close permanently. There’s no other option,” she says distraught.

Another businesswoman by the name of Erkezhan is also concerned about her company’s future. “My friends and I arrange different types of events: weddings, corporate events, team-building exercises, sports events. But now everything has been cancelled and people are reclaiming their deposits. The main problem is that we have to return deposits that have already been handed over to performers and event leaders. And people don’t want to give them back. But we don’t have the right to just take the money ourselves because the current crisis is a force majeure. Designers and decorators will take a cut and hand over work already done. Performers are willing to return deposits, but not immediately. We’ll have to ask our clients to wait. To get through this situation, you basically have to be a psychologist and a lawyer at the same time,” Erkezhan says.

Above all, however, she is worried that event organisers and leaders, performers, musicians, photographers and film crews, decorators and designers will all be left without work. “More importantly, after the end of the lockdown there will still be a crisis. People won’t be in the mood for celebrations and events. That means another six months without work. But the worst thing is simply not knowing. Nobody knows when things will return to normal. It seems like we’ll all have to take up a new profession or polish up on old skills,” she says pensively.

Elena Iskhakova runs a beer firm that the government has forced to close. She is far from happy with this decision. “Beer and associated products are foodstuffs, but some municipal officials don’t see it this way. You can thrust the relevant law text right in front of their noses, they don’t care. Even though the Chamber of Entrepreneurs also considers the closure unlawful and the words used by the mayor support our cause, some people in subordinate positions don’t seem to see this and go around threatening and bullying people, intimidating them with threats of SES (Sanitary-Epidemiological Service) inspections,” the entrepreneur fumes.

Meanwhile, Kazakh businessmen have appealed to the country’s president to draw up sufficiently firm and radical measures to not only allow the stabilisation of the small and medium-sized business sector but also ensure its long-term development. Tokayev quickly responded to the appeal and acknowledged that the complaints it contained were justified.

Bagdat Asylbek

Translated and adapted by Nick L.

-

09 August09.08The two deportations of YaghnobDeep in the Tajik mountains live the last bearers of the dying language and culture of the ancient Sogdians

09 August09.08The two deportations of YaghnobDeep in the Tajik mountains live the last bearers of the dying language and culture of the ancient Sogdians -

06 August06.08What went wrong in Central Asia’s coronavirus response?How poor planning and a fixation on faulty test results undid months of hard work

06 August06.08What went wrong in Central Asia’s coronavirus response?How poor planning and a fixation on faulty test results undid months of hard work -

31 July31.07“Another week and I wouldn’t have got out of there alive”Why patients in Uzbekistan fear ending up in hospital, and medics fear the end of the lockdown

31 July31.07“Another week and I wouldn’t have got out of there alive”Why patients in Uzbekistan fear ending up in hospital, and medics fear the end of the lockdown -

30 July30.07“The number of graves now is 15 times greater”Lebap region residents told to hide new graves from satellite imaging amid more reports of chaos in Turkmenistan’s COVID-19 response

30 July30.07“The number of graves now is 15 times greater”Lebap region residents told to hide new graves from satellite imaging amid more reports of chaos in Turkmenistan’s COVID-19 response -

25 July25.07Slaying the hydraWhy the coronavirus has been winning in Kyrgyzstan

25 July25.07Slaying the hydraWhy the coronavirus has been winning in Kyrgyzstan -

21 July21.07War of worldsThe first public protest action in Uzbekistan in defence of women’s rights met with an aggressive reaction from much of society

21 July21.07War of worldsThe first public protest action in Uzbekistan in defence of women’s rights met with an aggressive reaction from much of society