👉 This article is also available in Russian, French, German, Spanish, Italian, and Chinese.

In 1996, Uzbekistan widely celebrated the 660th anniversary of Amir Timur’s (Tamerlane’s) birth. On October 18 that year, then-President Islam Karimov awarded the city of Samarkand the Order of Amir Timur, and the same date was declared Samarkand Day. This year’s celebration will be especially significant — the city turns three thousand years old. Of course, that number is approximate and rounded, but it broadly aligns with the most recent scientific findings.

The difference between a city and a woman

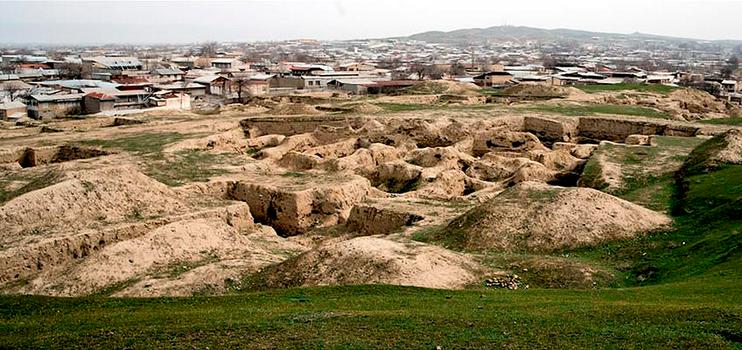

Research into the history of Samarkand has been ongoing for about 150 years. Initially, scholars assumed the city was no more than 1,500 years old. But as archaeological research expanded and science advanced, the city’s age was repeatedly revised. It quickly reached two thousand years; by 1970, it was estimated at 2,500 years, and by the early 2000s — 2,750. However, recent excavations in the Afrasiab and Kuktepa areas, carried out by an interdisciplinary team of researchers, have made it possible to assert that Samarkand is at least three thousand years old.

Although the most beautiful cities are sometimes compared to women, there are some differences between them. It is generally believed that a woman is more attractive the younger she is, whereas with cities, the opposite is true: the older a city, the better. Thus, thanks to the latest scientific findings, Samarkand has “aged” — and its image, without a doubt, has only improved. To prevent detractors and lovers of cheap hype from diminishing the city’s significance or making it seem younger than it truly is, the people’s deputies of the Samarkand region passed a legislative resolution declaring that Samarkand’s official age is now three thousand years.

Naturally, some reacted to this decision with irony, suggesting that in the past 150 years, the city has managed to grow twice as old — and that if we wait a little longer, its age might surpass that of the Earth, and, with luck, even that of the entire galaxy.

Many were also reminded of how, in 2016, Mirfatykh Zakiev, a full member of the Academy of Sciences of Tatarstan, claimed that Kazan was not one thousand years old, as Soviet scholars had maintained, but more than 2,700. His colleague, Fayaz Khuzin, deputy director of the Khalikov Institute of Archaeology, countered that traces of an ancient settlement in the area did not necessarily mean that a city existed there at the time.

That argument, however, clearly does not apply to Uzbekistan’s long-lived city. A joint Uzbek-French expedition reexamined earlier findings and concluded that by the beginning of the first millennium BCE, Samarkand had already emerged as a major urban center with palaces and temples.

Even without taking into account the findings of the French-Uzbek scientific expedition and the regional deputies who endorsed them, the antiquity of Samarkand is beyond dispute. Even according to the previously accepted version, the city dates back to the 8th century BCE and is thus a contemporary of ancient Rome. Yet while the Eternal City was founded by Romulus and Remus — brothers raised by a she-wolf, whose origins perhaps determined its inherently militaristic and colonial nature — the creation of Samarkand is attributed (according to one version) to a man named Samar. He is said to have established a settlement here that drew people from the surrounding area. The legend preserves no record of this remarkable man’s occupation, but most likely Samar was a merchant or farmer who could exchange his surplus goods with others — otherwise, why would people have come to him?

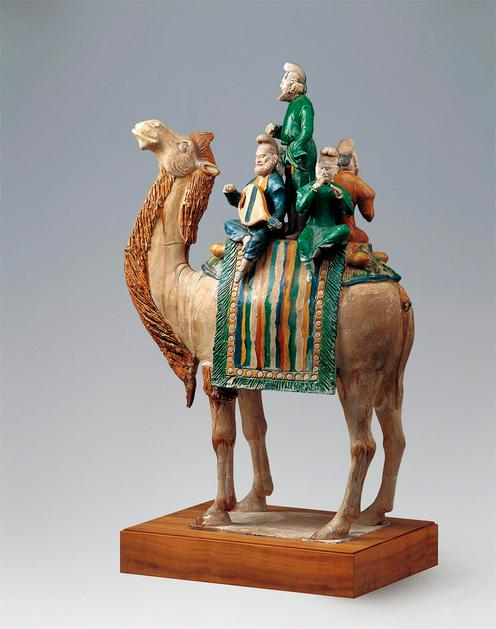

For more than two millennia, the city was one of the key points along the Great Silk Road, which linked trade between China and Europe. Samarkand even earned the honorary title “the heart of the Great Silk Road.”

As befitted a trading city, Samarkand grew rapidly, strengthened, and became the capital of Sogdiana. Naturally, the flourishing city did not escape the attention of Alexander the Great. In 329 BCE, Samarkand — known to Roman and Greek historians as Maracanda — was captured by the Macedonian’s army.

However, Maracanda, or Samarkand, despite its peaceful mercantile character, proved to be a tough nut even for Alexander. The distinguished Sogdian commander Spitamenes led a rebellion against the foreign conquerors. During an epic battle near the Zeravshan River, not far from Samarkand, Spitamenes routed the troops led by Greek and Macedonian generals. This is considered to have been Alexander’s first major defeat in seven years of military campaigns.

Realizing that the Samarkandians were formidable opponents, Alexander was forced to take personal command of his army. Fearing that even this might not be enough, he resorted to diplomacy — forging ties with Sogdian and Bactrian aristocrats and plotting against Spitamenes. Betrayed by his own allies, the Sogdian commander fled to the Massagetae, only to be betrayed again and killed by the tribal leaders.

In the following centuries — the 4th and 5th CE — Samarkand fell under the rule of nomadic tribes. In the 6th and 7th centuries, it became a vassal of the Turkic and Western Turkic Khaganates.

At the beginning of the eighth century, the city was captured by Arab conquerors, and in the middle of the century, Abu Muslim — the governor of Khorasan and Transoxiana — made Samarkand his residence. Although uprisings against foreign invaders occasionally broke out, the city was never particularly warlike. Perhaps that was what made it so attractive to people: life is better when there is peace, not war. War is only good if one wishes to die; life is good in peace — simple maxims understood by people in any age.

Once again, in the 770s, Samarkand was chosen as a capital — this time of the Samanid state. The Arab geographer Abu al-Qasim Muhammad ibn Hawqal described the city of that time as follows:

“Samarkand is a city with large markets and, like other great cities, many quarters, baths, caravanserais, and houses. It has running water brought in through a canal, part of which is made of lead. A dam has been built upon it, rising above the ground in some places. The center of the market and the money-changers’ quarter are paved with stones, over which water flows from the coppersmiths’ district and enters the shahristan through the Kesh Gate… With few exceptions, there is not a single street or mansion without running water, and only a few houses lack gardens… Samarkand is the center of refined people in Transoxiana, and the best among them were educated in Samarkand.”

This description is no coincidence — in those times, Samarkand was truly the jewel of the territories later known as Central Asia. Science, poetry, and architecture flourished there. The Samarkand of the Samanid era was home to poets such as Rudaki and Ferdowsi, to the great philosopher and scholar al-Farabi, and to a number of eminent Islamic theologians.

Before the Face of Genghis Khan

In the 11th–13th centuries, the great city became the capital of the Western Karakhanid Khaganate. States and dynasties changed, yet Samarkand remained a center of scholarship, literature, and religious thought. During the reign of Shams al-Mulk, Omar Khayyam was invited to the court in Samarkand, where the great poet and scientist wrote his principal mathematical work, On the Proofs of Problems in Algebra and Al-Muqabala.

In 1212, the city came under the rule of Ala al-Din Muhammad II, the Shah of Khwarazm, but his control was short-lived. In 1220, Samarkand was attacked by the armies of Genghis Khan. After a three-day siege, the city fell and was utterly devastated. At that time, Samarkand had a population of about one hundred thousand families. Following its capture, roughly three-quarters of the inhabitants were killed or enslaved. The Mongol invasion destroyed nearly all the architectural masterpieces created in earlier centuries.

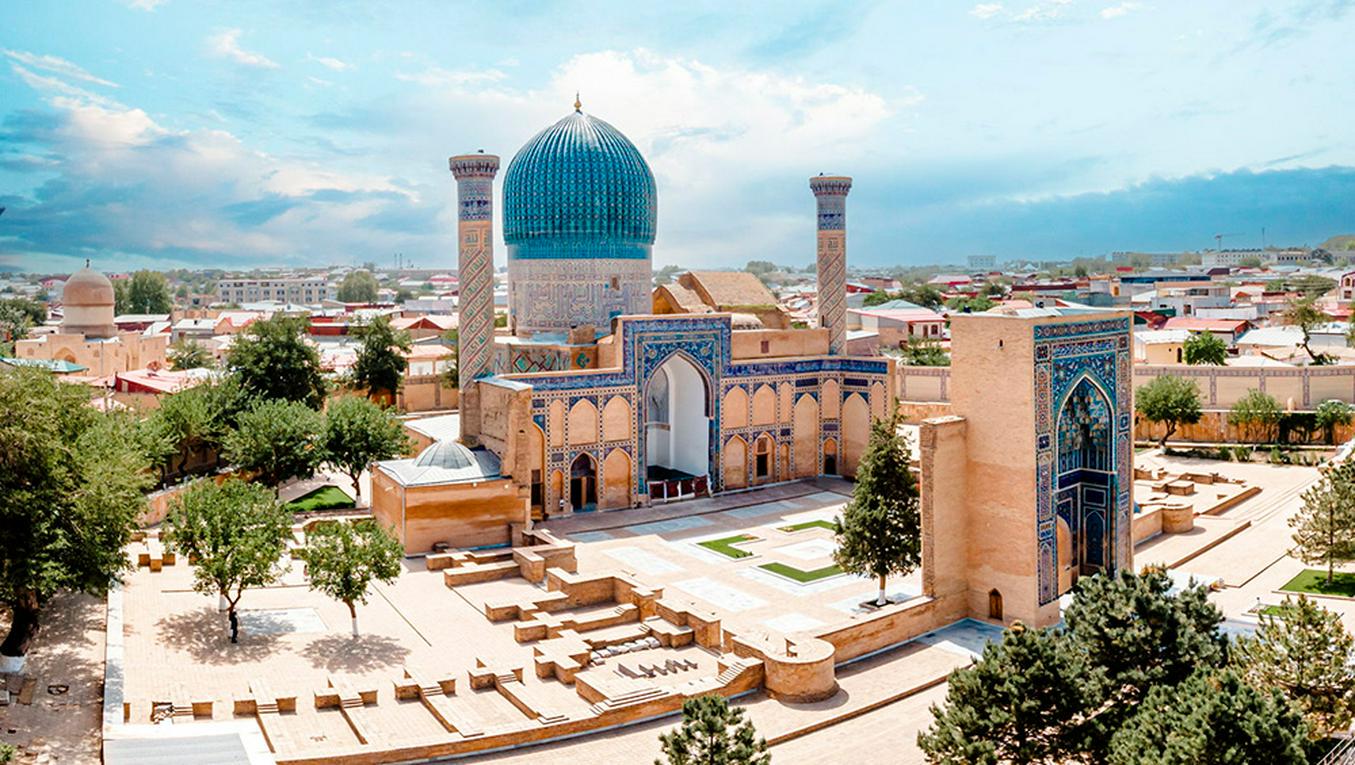

Samarkand experienced a new rise under Amir Temur. From 1370 to 1499, it was the capital of the Timurid Empire. It is generally believed that most of the architectural masterpieces that have survived to this day were built during this era. Amir Temur wanted his capital to become the capital of the world, and even gave the nearby villages the names of famous cities of the East—Baghdad, Shiraz, Damascus. Prominent poets, musicians, scholars, and theologians from many countries flocked here. Magnificent gardens with palaces and fountains were laid out, and their gates were open even to ordinary people. Under Temur, Samarkand became the trade center of Central Asia. Moreover, the legendary ruler took care to improve sacred sites for Muslims. Amir Temur gathered not only scholars and artists but also craftsmen from different lands who rebuilt and decorated his capital. It is no wonder that the city of clay became a city of stone—and one of the most beautiful at that.

The flourishing and embellishment of Samarkand continued under Temur’s descendants. Among them, special mention must be made of the poet, thinker, and historian Zahiriddin Muhammad Babur, ruler of India and Afghanistan, founder of the Mughal dynasty and the Mughal Empire. In his famous work Baburnama, he wrote:

“Samarkand is an extraordinarily well-arranged city, and it has a special feature that is rarely found elsewhere: each craft has its own bazaar, and they do not mix with one another—this is the rule. There are excellent bakeries and eateries. The best paper in the world comes entirely from Kan-i-Gil, which is on the bank of the Siyah-Ob stream; this stream is also called Abi-Rahmat. There is another Samarkand product: crimson velvet; it is sent to many places.”

The Curse of Amir Temur

At the beginning of the 16th century, Samarkand became the capital of the Bukhara Khanate. Even after 1533, when the capital was moved to Bukhara, all the khans continued to be crowned in Samarkand, in the palace of Kuksaray. It was here that the “Kuk-Tash,” the stone throne of Amir Temur’s era, was kept. The tradition of coronation in Samarkand continued until the reign of the Emir of Bukhara Muzaffar (1860–1885).

The city continued to thrive and attract minds and talents from across Asia during the era of the Uzbek Ashtarkhanid dynasty.

In 1740, the Iranian ruler Nadir Shah attacked Samarkand. From the city, he took the jade tombstone of Amir Temur to Mashhad. According to legend, the disturbed spirit of Temur appeared to him in a dream. Soon after, terrible calamities began to plague the country—from earthquakes to epidemics—and several assassination attempts were made on Nadir Shah’s life. Frightened, the ruler ordered the tombstone to be returned to Samarkand and placed back in its original position in the Gur-Emir mausoleum. Nevertheless, it did not save him—he was brutally killed in 1747.

Interestingly, talk of the “curse” of Temur’s tomb resurfaced in the 20th century. According to legend, Hitler decided to attack the USSR right after Soviet archaeologists opened Tamerlane’s tomb. Of course, academic historians deny any link between these events.

By the mid-18th century, Samarkand had been destroyed and fallen into desolation. It began to recover only decades later, thanks to the efforts of Muhammad Rahim-Biy, founder of the Uzbek Manghit dynasty, and Emir Shahmurad. Due to their efforts and those of later rulers, Samarkand was gradually rebuilt and revived in the 18th and 19th centuries.

In May 1868, the city was captured by the Russian army under General Konstantin Kaufman. That same year, when Russian forces advanced to pursue the Emir of Bukhara, only a small Russian garrison was left in the Samarkand fortress. It numbered no more than seven hundred men, armed only with rifles, mortars, and two Russian cannons. There were 24 Bukhara cannons in the city, but they had been spiked and rendered unusable.

Taking advantage of the situation, an entire army of local tribes—numbering, according to various sources, from 40,000 to 65,000 men—approached Samarkand. Almost simultaneously, an uprising against the new Russian authorities broke out in the city.

Realizing that it was impossible to defend the city with the available forces, the commandant, Friedrich von Stempel, decided to barricade himself in the fortress and hold out. Among the defenders was the future famous artist Vasily Vereshchagin, who later described the events in his book At War in Asia and Europe.

Before long, Samarkand was divided into so-called “native” and European (Russian) parts. The city underwent significant reconstruction and renewal.

The Journey of the Uthman Quran

Shortly after the October Revolution of 1917—in April 1918—the Turkestan Soviet Republic was proclaimed. This period saw a curious historical episode. In 1869, the governor-general of Turkestan, Konstantin von Kaufman, sent a Muslim relic to St. Petersburg: the famous Uthman Quran, which had been kept in Samarkand and, according to legend, was stained with the blood of the third righteous caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (575–656). However, in 1923, at the request of the ulema (Islamic scholars) of Tashkent and Jizzakh, the Soviet government returned the Quran of Uthman. In August 1923, it was transported in a special railway car to Tashkent and then to Samarkand, to the Khodja Ahrar Mosque.

Restorers examine the Uthman Quran, 2024. Photo: Press Service of the Art and Culture Development Foundation of Uzbekistan

Restorers examine the Uthman Quran, 2024. Photo: Press Service of the Art and Culture Development Foundation of Uzbekistan

In 1924, the plan for national-territorial delimitation was implemented, resulting in the dissolution of the Turkestan Republic and the formation of several Central Asian republics, including Uzbekistan. From 1925 to 1930, Samarkand served as its capital, before the status was transferred to Tashkent.

During World War II, Samarkand, like many other cities of Soviet Central Asia, became one of the main evacuation centers. The city welcomed many people and institutions relocated from the western parts of the USSR, offering them refuge from the war.

After the war, and up until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Samarkand saw rapid development in both domestic and international tourism. Industrial enterprises and factories were established, turning the city into one of the region’s major industrial centers.

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Samarkand became the administrative center of the Samarkand region in independent Uzbekistan. The country’s first president, Islam Karimov, was himself a native of Samarkand and paid special attention to the ancient city throughout his presidency. Monuments were erected here to Amir Temur, the great poets Alisher Navoi and Rudaki, the scholar and ruler Mirzo Ulughbek, and the eminent Islamic thinkers and theologians al-Bukhari and al-Maturidi.

For the current president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Samarkand is also a familiar city. From 2001 to 2003, he served as the hokim (head of administration) of the Samarkand region. Under his presidency (he officially took office in 2017), the city’s political significance has grown substantially. Samarkand now regularly hosts international summits and conferences of various scales and agendas. Notably, in September 2022, the city hosted the 22nd summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

The year 2025 in Samarkand has been marked by several major conferences. In April, it hosted the first “Central Asia – European Union” summit. In October, Samarkand was the venue for a meeting of the Council of Heads of Security and Intelligence Agencies of the CIS member states. From October 13 to 17, 2025, the city held the 10th anniversary General Assembly of the Silk Road Universities Network (SUN). And at the end of the month, Samarkand will welcome the 43rd session of the UNESCO General Conference—the largest humanitarian event of the decade.

Samarkand continues to serve as a cultural and artistic hub. In 2024, it was recognized as the Cultural Capital of the Commonwealth of Independent States, and in May 2025—as the Cultural Capital of the Islamic World. The city has nearly thirty twin cities across the globe. It is home to dozens of historical landmarks, including the architectural ensemble of Registan, the ancient site of Afrasiab, Ulughbek’s observatory and museum, the mausoleum of Amir Temur, and many other monuments of regional and global significance. Moreover, its architectural treasures are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Thus, it can be said with full confidence that on the eve of its anniversary, this ancient city is once again experiencing a renaissance—one of many over its three-thousand-year history, and hopefully not the last.

-

14 February14.02From Revolution to Rupture?Why Kyrgyzstan Dismissed an Influential “Gray Cardinal” and What May Follow

14 February14.02From Revolution to Rupture?Why Kyrgyzstan Dismissed an Influential “Gray Cardinal” and What May Follow -

05 February05.02The “Guardian” of Old Tashkent Has Passed AwayRenowned local historian and popularizer of Uzbekistan’s history Boris Anatolyevich Golender dies

05 February05.02The “Guardian” of Old Tashkent Has Passed AwayRenowned local historian and popularizer of Uzbekistan’s history Boris Anatolyevich Golender dies -

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

24 November24.11Here’s a New TurnRussian Scientists Revive the Plan to Irrigate Central Asia Using Siberian Rivers

24 November24.11Here’s a New TurnRussian Scientists Revive the Plan to Irrigate Central Asia Using Siberian Rivers -

11 November11.11To Live Despite All HardshipUzbek filmmaker Rashid Malikov on his new film, a medieval threat, and the wages of filmmakers

11 November11.11To Live Despite All HardshipUzbek filmmaker Rashid Malikov on his new film, a medieval threat, and the wages of filmmakers