As is well known, the Chinese do not place much trust in foreigners, even referring to them among themselves as «gui»—devils. However, there is a time of year when even the most law-abiding Chinese citizen and the most cunning foreign «devil» come together in a shared spirit. This time is known as the Chinese New Year, or Chūn Jié, also called the Spring Festival, celebrated according to the lunar calendar.

Green, Blue, or Black?

Unlike the standard New Year, which arrives with unwavering consistency on the night of December 31 to January 1, the Chinese New Year comes whenever it pleases—or more precisely, anytime after the winter new moon, falling on a date between January 21 and February 20. This year, the Spring Festival arrives early, celebrated on January 29.

Even those with little knowledge of Chinese astrology know that 2025 will be the Year of the Green Wooden Snake. Of course, no such fantastical creature exists in nature, even in China. Instead, this designation combines the symbolic elements used to characterize the incoming year: an animal, a color, and one of the five fundamental elements in Chinese tradition—fire, water, wood, metal, and earth.

Thus, in 2025, the dominant animal is the snake, the primary element is wood, and the main color is green. However, some sources may claim that this year’s snake is not green but turquoise, blue, or even black. This naturally raises a question: which color is the «correct» snake, and which are mere imitations?

The answer is simple—all of them are correct. The confusion arises because the Chinese character 青 (qing), which defines this year’s color, encompasses a broad spectrum, ranging from deep blue to black. Therefore, when translating, one is free to choose whichever shade feels most fitting.

They Spit and Act Up

As the Year of the Snake approaches, it’s worth understanding how the Chinese themselves feel about this animal. Strangely enough, there isn’t a single clear answer.

On the one hand, the snake is associated with wisdom, caution, and the ability to strike at the right moment—traits that, according to the Chinese, humans can learn from the reptile. Additionally, due to its unique physiology, the snake can slip through almost anywhere, a characteristic that also resonates with the Chinese and aligns with their national character.

On the other hand, a snake is still a snake—an elusive, dangerous, and often venomous creature. You never quite know why it slithers up to your feet—whether it’s just expressing respect or hiding some subtle hostility, a trait common to all reptiles but especially to snakes.

Finally, when prepared correctly, snake meat is considered delicious and beneficial for health, which adds to its appeal—particularly among southern Chinese people.

In northern China today, it’s almost impossible to spot a wild snake aimlessly wandering through the vast expanses. However, in ancient times, the valleys of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers were swampy, forested areas densely covered in vegetation, and snakes were abundant. But the restless Chinese people quickly cleared the forests, drained the swamps, and ate the snakes. Now in the north, you might only find this charming reptile in a zoo, as a dried specimen in a pharmacy, or skewered on a street food stick.

However, snake skewers are still considered exotic. For one, it’s a poor cooking method: snakes cooked this way end up tough, rubbery, and unpleasant. Additionally, modern young Chinese prefer more familiar, «civilized» meats—pork, lamb, chicken, not to mention seafood.

In the south, however, snake meat is still enjoyed. Russian tourists who visited Guilin in the early 2000s likely encountered a Chinese guide with the Russian name Pyotr. According to him, Pyotr had read all of Dostoevsky in the original, a feat that’s elusive for most Russians. Apparently, the great Russian writer left such an impression on the poor guide that, during tours, Pyotr would burst into nervous laughter. But what the tourists remembered most wasn’t his laughter, but his candid confession. When a Russian tourist, somewhat nervously surveying the surrounding mountains, asked if there were many snakes there, Pyotr regretfully replied that there used to be many, but not anymore.

— Where did they all go? the tourist asked.

— They all got eaten, Pyotr replied, licking his lips. They’re so tasty. Now they’re only delivered from the farm.

However, if all the wild snakes were eaten, it wasn’t everywhere and not all of them. To this day, in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, there’s still a profession of snake catchers. They typically work in the mountains, where a specific species— the black spectacled snake, also known as the Chinese cobra—can be found. Snake catchers claim that these snakes—called extremely fierce in Chinese—are not to be trifled with. If the stories are true, these particularly fierce snakes are not only highly aggressive but also possess a potent venom and, on top of that, are very accurate with their spitting, aiming straight for the eyes.

There are rumors that in the past, woodcutters had a hard time with Chinese cobras. The poor men claim that if they accidentally disturbed a snake, it would immediately charge at them with the fiercest expression. Naturally, the woodcutter would run, but the rebellious reptile would chase after him. It is said that to get rid of such a snake, they had to run through several mountain gorges or until they encountered a snake catcher who would capture the audacious creature.

However, these stories are less believed now. It is thought that the woodcutters may have confused several snakes for one, chasing after them. Yet, judging by the reputation of Chinese cobras, they could very well be capable of such antics.

In the past, when cobras were caught, tradition dictated that they not be killed immediately. Instead, they were placed in special metal cages. While they couldn't escape, they would angrily spit at unsuspecting passersby—a spectacle in itself.

Snake Vodka

In the past, when a customer purchased a snake, after the reptile was butchered, they would usually return the skin and gallbladder to the seller. These were dried and sold for a good price at specialized collection points. Snake bile is still considered an excellent medicinal remedy in Chinese medicine. Additionally, according to folk beliefs, eating a snake’s vertebra can cure leprosy.

More often than not, snakes are either boiled or used to make soup. When this is done, the bones are removed from the reptile, and then a hidden spot is found in the backyard to bury them. This ritual stems from the belief that if someone pricks themselves with a snake bone, they will never be cured of any disease. In modern terms, the belief is that a snake bone prick weakens the immune system in a way similar to how HIV/AIDS affects it. However, this tradition originated in China long before AIDS was discovered.

It is known that in Guangdong Province, eating snakes has been a practice since ancient times. For example, in the text Huainanzi from the Western Han era (over two thousand years ago), it says: «The southerner caught a python—he will indulge in a delicacy.» However, considering the size of the python, it was always hard to predict who would end up eating whom—the southerner the python, or the python the southerner.

In the late 20th century, during socialist China, snake meat was not commonly consumed, and therefore, it was very cheap in Guangdong Province. For instance, in 1985, a Chinese customer bought 2.5 kilograms of snake meat for just five yuan in the city of Jin Xin (at that time, five yuan could barely buy one kilogram of pork). He then hosted a lavish meal for his friends from capitalist Hong Kong, where snake meat was quite expensive and considered a delicacy. However, after Deng Xiaoping stepped down and China began undergoing changes, snake meat prepared in a Chinese hotpot (hogo) became highly popular.

Regardless, snakes have once again become a part of the culinary scene, used in medicines, marinated in bottles filled with alcohol or wine. In the early 2000s, tourist boats on the Lijiang River offered tastings of snake-infused vodkas and wines. Few Europeans or even northern Chinese would dare to try such an attraction, but surprisingly, snake vodka became quite popular among Australians.

Interestingly, in China, both wine and vodka are infused not only with small poisonous snakes but also with large adult pythons. Of course, they aren’t placed in regular bottles, but in gigantic glass containers, sometimes as large as a human.

Snakes have left a notable mark not only on Chinese cuisine but also on Chinese literature. One of the most romantic stories in medieval China is The Legend of the White Snake. According to Daoist beliefs, if an animal practices Daoist magic, improves itself, and lives out its natural lifespan, it can transform into a more significant being, become human, and even attain immortality. The legend of the White Snake tells the story of such a magical snake that could transform into a young woman. She fell in love with a man named Xu Xian, but their love was blocked by a terrifying shape-shifting tortoise. The tortoise vowed to destroy the White Snake and nearly succeeded.

The story is set in Hangzhou, which is no coincidence. Hangzhou marks the boundary where snakes began to play an increasingly important role, both in reality and in the consciousness of the Chinese. Many films and performances have been made about the Legend of the White Snake, including puppet shows and even shadow plays. A production starring the famous Chinese actor Mei Lanfang exists, and it’s said that Charlie Chaplin himself saw the performance and praised it highly.

In fact, anyone learning Chinese will encounter the snake early on. In almost every Chinese language textbook for foreigners, there's a common expression: huà shé tiān zú (画蛇添足), which literally translates to «drawing legs on a snake,» meaning to do unnecessary work that spoils the result.

In the famous genre of Chinese «unfinished sayings,» the snake also makes appearances:

«The snake eats the eel, measuring its length (otherwise it may not fit completely).» This saying implies the need to act according to the situation.

«The snake crawls inside the bamboo tube — every coil is difficult.» This suggests a situation where a person faces difficulties in everything they do.

«The snake has entered the bamboo tube — there’s no way but forward (no turning back).» This means there’s no other option but to proceed down the current path.

The Day of The Singer

However, snakes have not only fascinated the Chinese from a culinary and medicinal perspective. Records show that as early as the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), enlightened individuals began rejecting snake meat and worshipped the snake as an embodiment of a divine spirit.

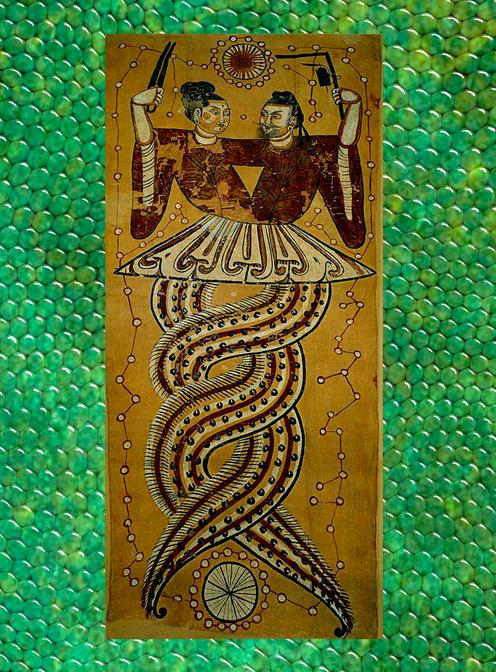

This may reflect even older cults linked to Chinese mythology. The legendary ancestors of the Chinese people, Nuwa and Fu Hsi, are often depicted as half-human, half-snake figures. Their bodies and heads are typically human (sometimes bovine), but their lower halves are serpentine. In Han dynasty tombs, there are reliefs showing Nuwa and Fu Hsi intertwined with their serpentine tails. Fu Hsi, as the male figure embodying the yang principle, holds the sun, while Nuwa holds the moon.

According to other Chinese beliefs, the snake is seen as a small dragon. In fact, Chinese dragons have a serpentine body and are closely associated with water, much like snakes.

In every Buddhist temple in China, there are four heavenly kings, gods who protect the four cardinal directions. One of them, the ruler of the West, is accompanied by a large snake. In the famous Chinese animated film The Monkey King (also known as Havoc in Heaven), the snake attempts to capture and devour the Monkey King, Sun Wukong.

In Guangdong Province, there is a temple called the Green Dragon Temple, where a snake spirit is worshipped in the form of a dragon. Before the formation of the People's Republic of China in 1949, every second month of the year featured a Dragon Festival. During the festival, the snake statue was paraded through the streets, accompanied by musicians and dancers who carried paper, fabric, and other material snakes. Special actors donned silk costumes, painted their faces in a serpentine style, and held a massive golden snake.

Before 1949, the procession allowed participation from women of lower social standing. These women dressed in their finest gowns and paraded alongside the divine snake, just like ordinary citizens. This is why the festival had a second name: Jinyu de jieji which translates to “Day of the Singer” or, more bluntly, “Prostitute’s Day.” These jinyu were somewhat similar to Japanese geishas, as they entertained men. However, in addition to this role, they also provided intimate services.

The question arises — why were the women referred to as singers in relation to the holiday? It seems that the Chinese saw a parallel between the prostitute and the snake. Both are creatures who do not display themselves unnecessarily. Furthermore, the snake can bite, and the prostitute — infect.

After the establishment of the republic, prostitution was banned, and the snake parades came to an end. However, by the late 20th century, the Dragon Festival was revived with great fanfare. Now, instead of prostitutes, the procession featured well-meaning builders of Chinese communism and organized old ladies, who enthusiastically danced with fake snakes in hand. Some Chinese joke that these aren't just old ladies, but rather the same jinyu who have simply aged, though Chinese historical science does not support this version.

Finally, astrologers consider the Year of the Snake to be special. They believe it brings a desire for harmony and opens up new opportunities for people. However, when pursuing these opportunities, one should exercise caution and trust their intuition, much like the snake does.

We, for our part, wish all Fergana readers a happy, prosperous, and peaceful year, and may the Snake exhibit only its best qualities. Happy Spring Festival! Chun Jie Kuai Le!

-

14 February14.02From Revolution to Rupture?Why Kyrgyzstan Dismissed an Influential “Gray Cardinal” and What May Follow

14 February14.02From Revolution to Rupture?Why Kyrgyzstan Dismissed an Influential “Gray Cardinal” and What May Follow -

05 February05.02The “Guardian” of Old Tashkent Has Passed AwayRenowned local historian and popularizer of Uzbekistan’s history Boris Anatolyevich Golender dies

05 February05.02The “Guardian” of Old Tashkent Has Passed AwayRenowned local historian and popularizer of Uzbekistan’s history Boris Anatolyevich Golender dies -

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy -

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

17 December17.12Gulshan Is the BestYoung Uzbek Karateka Becomes World Champion

17 December17.12Gulshan Is the BestYoung Uzbek Karateka Becomes World Champion