The green economy is gradually ceasing to be an abstract concept and is becoming a practical instrument of industrial and regional policy. Amid climate risks, resource shortages, and aging infrastructure, this approach is increasingly seen as a way to reconcile economic growth with environmental constraints. In recent years, China has emerged as one of the world’s key centers for the development of the circular economy, which is an important component of its environmental agenda.

One of the flagship showcases of China’s green achievements is the Ziya Economic and Technological Development Zone (ETDZ)—a national industrial park for the circular economy specializing in waste processing, resource reuse, and the development of low-carbon industries. The zone is located in Tianjin, near Beijing. It is positioned as a China–SCO cooperation platform in green industry, a venue for joint projects, technology exchange, and the harmonization of standards in “green” sectors.

A Ferghana correspondent visited the zone during the international media tour Date with China, organized with the participation of the leading English-language Chinese outlet China Daily.

China is already working closely with Central Asian countries on the development of the green economy. Chinese companies, for example, have planned the construction and launch of a wind turbine manufacturing project in Kazakhstan. Uzbekistan is currently scaling up solar and wind generation and energy storage, with China acting as one of the investors; an agreement has also been signed for a 60 MW “green” project for Namangancement. In the autumn of this year, reports emerged that Chinese businesses would build a solar power plant in Kyrgyzstan. Projects with Tajik partners are also under discussion.

The circular economy is a model in which waste is transformed into secondary raw materials: materials are not discarded but collected, sorted, and recycled, returning them to industrial circulation and reducing the need for primary resources. This applies to municipal solid waste—discarded household appliances, vehicles, batteries, glass, plastics, and printed circuit boards. Recycled waste is processed into powders, fractions, or granules and sold to industrial consumers.

In China, this system is already in place, although, as business representatives note, it does not always generate superprofits for everyone, since much depends on scale and on how well the entire chain is structured—from waste collection to the production of new goods. Nevertheless, the sector remains promising and continues to attract sustained interest from China’s economic and political establishment. This is evidenced, in particular, by the active development of cooperation in the “green” economy within the SCO framework, including with Russia.

For Central Asia, mastering the circular economy is undoubtedly important. In the coming years, the region will inevitably face the same “resource” and infrastructure challenges as China: growing volumes of electronic waste, decommissioned household appliances, batteries, plastics, and, in the future, large quantities of end-of-life solar panels. This is something that needs to be addressed already today.

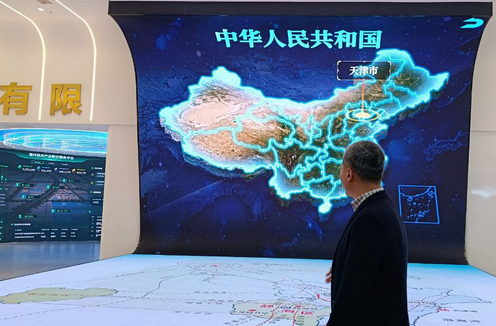

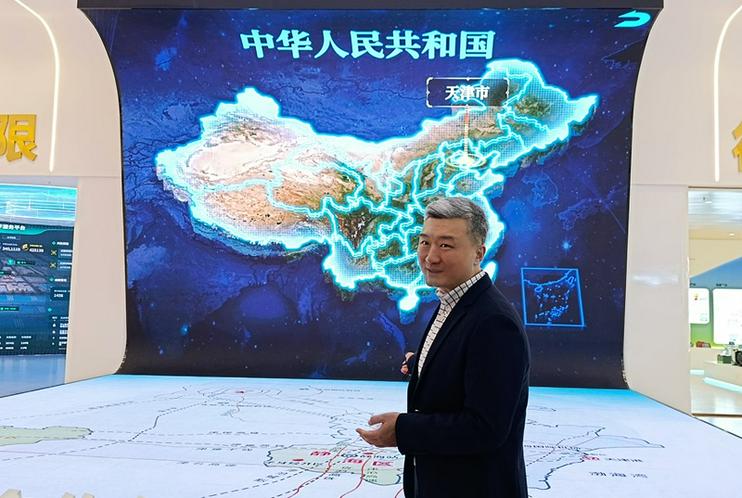

The tour for foreign journalists began with a visit to the circular economy exhibition hall at the Ziya ETDZ, where a Ferghana correspondent spoke with Zhao Shuang, Deputy Secretary of the Party Committee of the Ziya Zone Administrative Committee.

— How do you assess the level of development of the circular and “green” economy in Central Asia?

— Since the SCO Green Industry Cooperation Platform was established only recently—earlier this year—we do not yet have a complete picture of the baseline state of the sector in the countries of the region. Nevertheless, we are already actively studying the situation and looking for opportunities for cooperation, drawing on the models and practices we have developed.

— What might this cooperation look like in concrete terms?

— We are ready to share our experience in developing the circular economy and to offer advanced technologies that have been developed and implemented in China. This involves broad cooperation, including with industrial and municipal partners, to put green, circular, and low-carbon approaches into practice in Central Asian countries.

— Are there already examples of cooperation with foreign partners?

— Yes, there are. We are actively working with SCO partners, including Pakistan. Many companies that previously operated in the Ziya zone have already entered overseas markets and begun implementing circular economy projects abroad. This gives us grounds to speak of a strong start.

— Could you be more specific?

— For example, projects for processing municipal solid waste are already being developed in Pakistan, including the dismantling of household appliances and cables. These business models largely resemble the stages China went through in the early phases of the sector’s development.

— Is there similar interest from Central Asian countries?

— We see clear prospects for cooperation with Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and other countries in the region. Our goal is to transfer technological and managerial solutions in recycling, dismantling, and resource reuse to help raise the industrial level of these sectors and support green development.

— Which areas do you consider priorities?

— These include the recycling of household appliances, vehicles, and electronic waste, as well as the development of circular economy infrastructure. We are prepared to provide B2B-format services, help build production chains, and offer technological and service support.

— Are companies from Central Asia ready to invest in such projects?

— This is a key question. We understand that without the participation of local capital and business, sustainable development is impossible. That is precisely why we advocate an organic combination of Chinese technologies and experience with the local industrial ecosystem and social capital.

— What cooperation formats are you considering?

— Various models are possible: opening branches, establishing joint ventures, partnership arrangements, as well as a model in which local companies handle operations while we provide technologies, platform solutions, and service support.

What else can China offer the world in general, and Central Asia in particular? During a tour of the Ziya zone, foreign journalists were shown three enterprises operating in the circular economy sector, offering concrete examples of how China’s “green” industry functions in practice.

Household Appliances

TCL-AOBO operates large-scale facilities for recycling household appliances and electronics, plastics, printed circuit boards, and also runs a dedicated line for end-of-life photovoltaic modules. What matters here is not so much the raw figures as the underlying principle: the recycler serves a large regional market—Tianjin and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region—thereby creating the critical mass of feedstock without which a circular economy turns into a costly experiment. The company processes around 200,000 tons of waste electrical and electronic equipment annually.

Since its founding, the company has recycled more than 30 million units of various appliances and recovered a total of about 1 million tons of secondary materials, including metals, plastics, glass, and other resources. In addition, 1,200 tons of ozone-depleting substances have been safely disposed of—equivalent to a reduction of approximately 2 million tons of CO₂ emissions. The company’s registered capital at launch in 2009 stood at around $28 million, while revenue in 2024 alone reached approximately $123 million.

Journalists were shown the central control room, from which the entire production process is monitored—from the logistics intake point and unloading facilities to shredding lines and the packaging of fractions and powders ready for further industrial use.

Solar modules deserve special attention, as they are gaining increasing popularity across Central Asia. Sooner or later, these solar parks will be decommissioned, and the availability of facilities capable of accepting such equipment for recycling will help prevent the emergence of informal dumping sites.

Copper

Sinone’s operations cover the full cycle of innovative secondary resource processing—from collection and sorting to deep processing and the production of finished goods. The group’s product range includes high-purity copper rods, cathode and anode copper, aluminum and zinc ingots, steel billets, and other metal products. The copper rods are made from 100 percent recycled copper with a metal purity of up to 99.99 percent. The production line was developed jointly with the Italian company Propez and is considered among the most advanced in China. Annual output is about 120,000 tons, and the products are fully certified.

Company representatives noted that Sinone Group is actively involved in implementing China’s national strategy to achieve carbon neutrality and peak emissions, with a strong emphasis on green energy. The rate of waste reuse within the group’s production cycle reaches 99 percent. The company’s office building is designed as an exhibition space featuring metal art objects, underscoring the business’s attention to visual communication and branding. On a dedicated screen—serving as a reminder of the company’s purpose—a video is continuously displayed about the environmental and production monitoring system, Eye of the Earth.

For Central Asia, this is one of the most practical cases. The region does not need to replicate China’s scale to benefit: the logic of secondary metals hinges on organized scrap collection, quality sorting, transparency of material flows, and stable off-take. Under these conditions, recycling becomes a tangible tool of industrial modernization.

Batteries and Accumulators

Battery Science & Technology (BST) specializes in the deep recycling of lithium-ion batteries—from dismantling and crushing to the extraction of components from so-called “black mass” (lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, iron phosphate, and graphite) and the reintegration of these materials into the battery manufacturing cycle. The Ziya zone operates an automated battery dismantling and crushing line with a capacity of about 10,000 tons per year, which functions without prior battery discharge.

According to company representatives, the business remains low-margin at this stage. However, there is a clear plan to expand capacity by 2030, including the launch of an integrated deep-recycling project capable of processing up to 10,000 tons of black mass.

For Central Asia, the relevance of this experience is tied directly to the ongoing electrification of the economy. Electric buses, energy storage systems, and solar projects will begin generating significant volumes of spent batteries in the coming years. Without domestic recycling infrastructure, the region risks becoming dependent either on informal dismantling markets or on external contractors.

-

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

30 September30.09When Sea Becomes Fact of the PastWhy Tokayev Is Concerned About the Health of the World’s Largest Enclosed Body of Water

30 September30.09When Sea Becomes Fact of the PastWhy Tokayev Is Concerned About the Health of the World’s Largest Enclosed Body of Water -

17 September17.09Risky PartnershipWhy Dealing with China Is Harder Than It Seems at First Glance

17 September17.09Risky PartnershipWhy Dealing with China Is Harder Than It Seems at First Glance -

05 August05.08How Turkmenistan Lost Its Freedom of SpeechRuslan Myatiev discusses the past and present of censorship in the country

05 August05.08How Turkmenistan Lost Its Freedom of SpeechRuslan Myatiev discusses the past and present of censorship in the country -

18 June18.06Unconditional Eternal FriendshipWhat China Offers Central Asian Countries

18 June18.06Unconditional Eternal FriendshipWhat China Offers Central Asian Countries