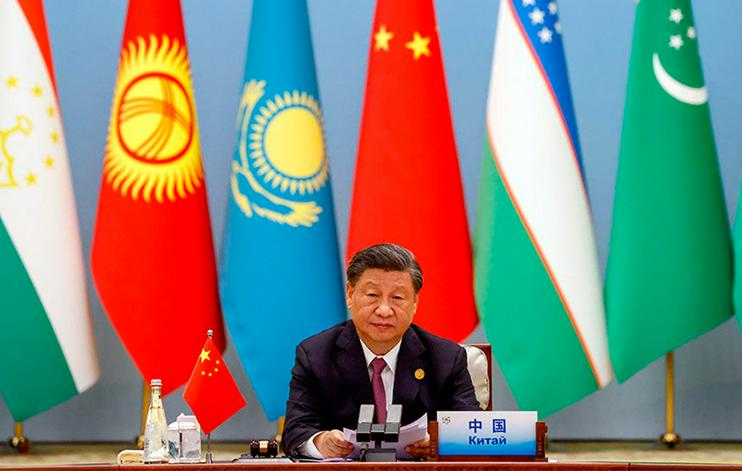

The recently concluded Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit outlined new prospects not only for Central Asian countries but for the world at large. Some even suggest that the summit was a bid to alter the existing world order. These assumptions are not accidental: during the summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping introduced the so-called Global Governance Initiative, which was notably supported by President Putin.

Experts interpreted this initiative as a shift in China’s approach to global politics. According to Vasily Kashin, director of the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies at HSE, the goal of the new Chinese initiative is the gradual transformation of global institutions and international behavioral norms—in essence, the creation of a new international order aligned with Chinese perspectives and interests.

Observers note that the SCO is moving from declarations toward institutionalization and the establishment of permanent bodies. Among them will be the Universal Center for Countering Security Challenges and Threats, to be located in Tashkent, and the SCO Anti-Narcotics Center in Dushanbe.

Western observers have reacted cautiously to Xi Jinping’s new proposals. Some even saw them as an attempt to replace the United Nations with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Such suspicions are, of course, promptly denied by both the Chinese themselves and their strategic allies, such as Russia. However, given recent developments—particularly India’s willingness to cooperate with China—the idea of a China-centered world operating in opposition to the West does not seem entirely far-fetched.

How such a world might function can already be inferred from the model of relations between China and Central Asia that has developed over recent years. This example clearly illustrates China’s economic, political, and humanitarian practices—at least from the perspective of non-Chinese observers.

Colonialism, Communist Style

In the 1990s, Russia was undoubtedly the main economic and political partner for Central Asia. By a habit inherited from the Soviet era, it was perceived as the metropolis, while the region’s republics were treated somewhat like provinces. Despite their legal and actual independence, these countries constantly looked to Moscow in politics, economics, and even daily life.

Sometimes the situation was almost comical. For instance, in the 1990s, Chinese-assembled computers in Kazakhstan were sold in stores at exorbitant prices. The reason was that Russian sellers bought the computers in China, shipped them to Moscow, where Kazakh businessmen purchased them, and then transported them to Kazakhstan—rather than importing them directly from China.

The Soviet legacy was so powerful that by the late 1990s it became clear that the young Kazakh intelligentsia often did not know their native language, having spoken and read only Russian all their lives. At that time, some senior executives in major Kazakh companies did not speak a word of Kazakh. Among young intellectuals and ordinary specialists, a movement emerged to study the Kazakh language. Along the way, there were unexpected cases: provincials and people from villages mocked the literary language of the youth, claiming it was “not real Kazakh.”

As the years went by, Russia continued to pursue its political and economic plans in the region. Meanwhile, China grew wealthier and gradually expanded its influence in Central Asia. At first, Beijing’s policy in the region was based on relatively straightforward objectives. In 2004, Chinese experts—namely Li Lifang, Deputy Director of the Research Institute of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and Ding Xiu, a researcher at the Central Asia Institute of Lanzhou University—formulated them as follows:

«After long research and careful preparation, Beijing’s Central Asian strategy has been defined. It aims to leverage the SCO… to advance its strategic interests, which are primarily focused on exploiting Central Asia’s resources.»

(Almanac China in World and Regional Politics: History and Modernity, Issue XIII [Special], Russian Academy of Sciences, 2008, p. 148)

By today’s standards, these objectives were distinctly neocolonial. In fact, despite its communist rhetoric, China in the 20th century clearly followed colonial trajectories. Criticism is difficult: the Chinese had to pull their country out of the abyss left by the catastrophes of the 20th century—the fall of the empire, civil war, and Japanese occupation. The Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and other Mao Zedong-era ideological campaigns did little to stabilize the nation. Deng Xiaoping’s reforms improved matters somewhat, but China was still far from not only the developed Western nations but even the so-called moderately prosperous society that Deng aimed to achieve.

At that time, the simplest and quickest path to wealth seemed to be exploiting external resources. This perspective largely shaped China’s policy toward Central Asia in the 2000s and 2010s.

At that time, the countries of the region were not only actively trading natural resources and controlling natural monopolies, but also taking loans from China. While this provided immediate benefits, it carried the risk of serious long-term consequences, up to and including potential losses of sovereignty. At least, this was the assessment of some political analysts and representatives of national socio-political movements.

Someone Is Always on Top

Despite the obvious benefits of cooperating with China, “Sinophobia” began to grow in Central Asian countries, particularly in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The reasons were varied, ranging from historical—such as the wars with the Dzungars, who had Chinese support—to political, linked to China’s treatment of certain ethnic minorities within its own borders, which included both Kazakhs and Kyrgyz.

However, the most immediate cause of Sinophobia was likely China’s policy in territories exploited by its companies. When establishing enterprises in Central Asia, the Chinese often brought in their own workers, depriving locals of coveted jobs. Even when locals were employed in Chinese-run enterprises, they were often treated as second-class citizens—at least that was how they perceived their treatment by Chinese management. From their perspective, a culturally alien Chinese worker occupied their jobs and profited from their natural resources.

The dissatisfaction of the average Kazakh manifested in anti-Chinese protests from 2016 to 2020. The largest wave occurred in the fall of 2019, beginning in the city of Zhanaozen. Residents opposed the construction of joint enterprises with China and called on the government to seek loans from Western countries instead. Protests against Chinese expansion were held in the capital and in several major cities.

Adding fuel to the fire was the dismissive and arrogant attitude of the Chinese toward local residents, which the locals naturally refused to tolerate. Of course, the treatment of ethnic minorities by the titular Russian nation during the USSR era was also far from exemplary, but at that time there was an official policy of equality among all peoples within the unified Soviet nation. There were plenty of rather offensive jokes about Georgians, Armenians, Chukchis, and so on, but people generally understood that they had to live together in one country. Against this backdrop, good working relationships and even friendships between people of different ethnicities were common. Xenophobia existed, of course, but it was usually “horizontal” in nature: we dislike them because we fear them or simply because they are strangers and it is unclear what to expect from them. It was partly offset by a shared language and common cultural background rooted in Soviet ideology. In any case, xenophobia was not allowed to run rampant—the all-seeing eye of the CPSU kept a close watch.

With the Chinese, things were different from the very beginning. In the 2000s, they arrived on the lands of Central Asian republics acting as if they were the masters and looked down on the local population. This behavior was not limited to ordinary Chinese workers and businessmen. In 2016, the then Chinese ambassador to Kazakhstan, Zhang Hanhui, who was displeased that Astana had tightened visa requirements for Chinese citizens, literally exploded, declaring: “This is very rude, it is humiliating! Do they (the Kazakhs) even know who they are dealing with?”

It is worth noting that this perspective of the Chinese toward other peoples and nations has certain historical roots.

The first and foremost reason lies in a hierarchical worldview deeply ingrained in Chinese culture. Traditionally, there were no truly equal partnerships—one side or one individual always occupied a higher position than the other. This extended to family relationships: in Chinese, for example, the word “brother” is rarely used on its own; a brother is always either older or younger, and the same applies to sisters. Even grandparents are not considered equal: ancestors on the paternal side are regarded as more important and significant than those on the maternal side.

This phenomenon developed over millennia. Originally, it was evidently linked to the ancestor-worship cult, where sacrifices were made by the eldest male in the lineage. Later, this order was reinforced by Confucian philosophy, which formulated the concept of xiao—filial piety and the subordination of the younger to the elder. The system typically encompasses family relations, the subordination of the lower to the higher, and the obedience of subjects to the ruler, who, according to the Chinese themselves, is the fumu—the father and mother of the entire Chinese people.

Han Chinese and Muslims

From the Chinese perspective, when they arrived in Central Asia with their projects and money, they naturally assumed the position of superiors, while those who worked for them—primarily local residents—occupied the position of subordinates. Subordinates, of course, were expected to obey and look up to their superiors.

It is worth noting that a distinctive feature of Chinese xiao is that in exchange for obedience and respect, the higher-ranking party provides protection and patronage to the lower-ranking one. However, this rule apparently did not fully apply to the inhabitants of Central Asia—again, due to the specifics of Chinese worldview.

According to ancient Chinese beliefs, the earth is square, covered by a round sky. The area beneath the sky is called the “Under Heaven” (Tianxia). At its center live the wise, highly cultured, and civilized Chinese. On the periphery, either partially covered or not covered at all by the sky, live barbarians of varying degrees of savagery.

And although this notion is, of course, archaic, the Chinese perception of their homeland as the center of the universe persists to this day. Barbarian peoples do not always deserve civilized treatment, and whether to grant them protection and patronage is left to the discretion of the Chinese. After all, they have already received payment for their resources and services—so what more do they deserve?

The situation was further complicated by the fact that the peoples of Central Asia have historically practiced Islam. For the Chinese, relations with Islam have long been ambiguous. On one hand, there are longstanding Muslim minority communities in China, usually referred to as the Hui. On the other hand, the average Chinese person traditionally viewed Muslims with suspicion because they abstained from pork—the staple meat in China—avoided alcohol, and rejected figurative art, which depicts humans and animals, something prohibited by the Quran. Additionally, by the Middle Ages, Muslims were very successful in trade and finance, which aroused Chinese jealousy and led to numerous mutual misunderstandings.

Finding the roots of the mutual distrust between the Han Chinese and the Hui Muslims is not particularly difficult. According to tradition, even Emperor Tongzhi (1861–1875) reportedly said that the Han despised the Hui simply for being Hui. This offended the Muslims and hurt their pride. To defend their social standing, they sometimes provoked the Han into conflicts and even physical altercations. At the same time, the ruling Manchu dynasty deliberately fomented tensions between the Han and Hui, ensuring that, weakened by internal strife, they would not direct their anger toward imperial authority.

It is possible that, even today, the Chinese have consciously or unconsciously transferred their suspicious attitude toward the Hui onto the peoples of Central Asia. In any case, arrogance and condescension are often present in interactions between Chinese and local residents.

However, Central Asia is not unique in this regard. The Chinese treat almost all foreigners in a similar way—that is, as barbarians. It is clear that this attitude is not characteristic of educated Chinese or the intelligentsia, who understand that every people and every country has its own culture and uniqueness, and therefore no reason exists to treat them with disdain. Yet China is not made up solely of intellectuals, and ordinary people enjoy demonstrations of Chinese superiority over foreign “savages.”

It is worth noting that such demonstrations can be sincere: ordinary Chinese truly believe that genuine culture and true civilization exist only among themselves. If you develop even a somewhat close relationship with a Chinese person, they will inevitably tell you that you need to study wénhuà—culture. Of course, they are not referring to your “barbarian” foreign culture, but to the real one: Chinese culture.

Can Soft Power Be Trusted?

Among the fears troubling citizens of states bordering China are the creeping takeover of their economies and the risk of losing territory. It cannot be said that these concerns are entirely unfounded.

After the collapse of the USSR, the Central Asian countries bordering China faced border issues. These were particularly acute in the case of Kazakhstan, with which China shares its longest border—1,740 km. By 1999, however, intensive negotiations had completed the delimitation of the China-Kazakhstan border. Under the agreements, 407 km² of disputed territory went to China, while 537 km² remained with Kazakhstan.

The China-Kyrgyzstan border was also fully delimited by 1999. Under two agreements, Kyrgyzstan ceded about 5,000 hectares of disputed land to China.

The most complex situation arose between China and Tajikistan. China claimed three disputed areas in the GBAO (Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region) totaling more than 20,000 square kilometers. According to various sources, China received between 1,000 and 1,500 square kilometers. For now, however, Beijing has not insisted on the immediate or unconditional fulfillment of its demands: Tajikistan already has a precedent of ceding disputed territory to China in order to repay debts.

However, China’s territorial claims on Central Asian countries also have deeper historical roots.

As is well known, vast territories east of China were once conquered by the Mongols. But the Mongol khans of that era were not just Mongols—they were emperors of China’s Yuan dynasty, from Kublai Khan to Togon Temür. In other words, several centuries ago, the territory of present-day Central Asia belonged to the Chinese-Mongol empire. The modern Chinese layperson is well aware of this and occasionally reminds others in private conversations or on online forums. Officially, of course, the Chinese government does not endorse such statements.

Territories, however, do not necessarily need to be seized—they can be leased or even purchased. And recently, China came close to such an opportunity.

Kazakhstan vividly recalls the wave of mass protests in 2016 against amendments to the Land Code. These amendments would have allowed agricultural land to be leased long-term or sold, including to foreigners. The mere possibility of significant territories falling under Chinese control alarmed the Kazakh population. The authorities ultimately decided not to go against public opinion, imposing a moratorium on the amendments and eventually banning the sale of land to foreigners altogether.

Nevertheless, China continues to exert pressure through what is known as “soft power,” a term popularized by Russian President Vladimir Putin. Perhaps it is precisely this soft power that most worries the average Central Asian citizen—and with good reason. Soft power works subtly, achieving its goals discreetly. In this sense, can soft power be trusted if it is impossible to know when it might turn into coercion? In some ways, soft power may be no better than brute force—and perhaps even more dangerous.

How, then, do the Chinese employ soft power in Central Asia, and how might they apply it in the wider world under new conditions? This is a discussion that deserves separate attention.

-

06 August06.08What went wrong in Central Asia’s coronavirus response?How poor planning and a fixation on faulty test results undid months of hard work

06 August06.08What went wrong in Central Asia’s coronavirus response?How poor planning and a fixation on faulty test results undid months of hard work -

31 July31.07“Another week and I wouldn’t have got out of there alive”Why patients in Uzbekistan fear ending up in hospital, and medics fear the end of the lockdown

31 July31.07“Another week and I wouldn’t have got out of there alive”Why patients in Uzbekistan fear ending up in hospital, and medics fear the end of the lockdown -

21 July21.07War of worldsThe first public protest action in Uzbekistan in defence of women’s rights met with an aggressive reaction from much of society

21 July21.07War of worldsThe first public protest action in Uzbekistan in defence of women’s rights met with an aggressive reaction from much of society -

25 June25.06ВидеоAn Uzbek firstTashkent sends troops to Russia’s Victory Day Parade for the first time. There they took part alongside their neighbours

25 June25.06ВидеоAn Uzbek firstTashkent sends troops to Russia’s Victory Day Parade for the first time. There they took part alongside their neighbours -

08 June08.06A very literal containmentHow Central Asia fought the coronavirus with quarantines, Part 2: Uzbekistan’s container camps

08 June08.06A very literal containmentHow Central Asia fought the coronavirus with quarantines, Part 2: Uzbekistan’s container camps -

28 May28.05Lobbying, Uzbek-styleA former State Tourism Committee official talks about a new project to attract foreign ideas and technologies

28 May28.05Lobbying, Uzbek-styleA former State Tourism Committee official talks about a new project to attract foreign ideas and technologies